Editor's note: This is the first of four installments in a year-long project looking at the effects of a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on Fort Wayne resident Connie Slagal.

Connie Slagal, 44, remembers being thin as a child, but the summer before third grade she suddenly put on weight and her doctor couldn't figure out why.

When she went back to school in the fall Slagal said her life had changed forever. But she was OK with the weight.

“I was comfortable with my weight; all through high school I was chubby, thick but not unhealthy,” said Slagal.

It wasn't until she was married and had her daughter that her weight passed the chubby phase. But she ignored it. In her mid-30s her doctors began to tell her she needed to control her weight; they warned her it would shorten her lifespan.

Slagal, a registered nurse, knew that, but hearing them say it scared her. So she began to work at losing the pounds. But every time she tried to lose weight she slimmed down to a certain point and then began to gain it back.

“I like being invisible, and this keeps me invisible,” Slagal said.

Slagal said she has never been comfortable with being the focus of attention.

Every time she would shed enough weight that people began to compliment her - women or men – she would start eating again.

“I had become a Type 2 diabetic,” she said.

Learning the costs

Slagal said she comes from a long line of overweight women who have low blood pressure and cholesterol. She had never had a motivator until she became diabetic. Her husband had never pushed her to lose the weight because he liked her the way she was. Now that it had become a health problem he became very supportive.

Connie Slagal, 44, a month after her Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass surgery. So far she has lost 37 pounds. Before surgery she weighed 307 pounds.

Connie Slagal, 44, a month after her Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass surgery. So far she has lost 37 pounds. Before surgery she weighed 307 pounds.Obesity related deaths account for 400,000 deaths each year in the United States. Only one in seven obese people will live an average life span. An obese woman's lifespan is reduced an average of nine years, for men, 12 years. In Indiana 65 percent of the population is overweight; 31 percent of that population is obese.“It wasn't until I went on the OPTIFAST weight loss program at Lutheran Hospital that I really lost some weight. In December of 2010, with that I lost 118 pounds,” Slagal said.

When she started the diet she weighted 407 pounds. Again Slagal said she became uncomfortable with the attention she began to receive and sabotaged herself to get back to that comfort zone. She put back on 50 pounds. She and her husband, Ron, talked about it and decided she needed to deal with the issues making her gain the weight back.

“We decided it would be better to deal with those issues of why I like staying invisible as opposed to dying young,” Slagal, said.

It was around that time she began investigating the surgical options. She decided on gastric bypass surgery. To qualify she needed to have a body mass index, BMI, of 40, which is considered extremely overweight. According to the Mayo Clinic website, the surgery is recommended to cure Type 2 diabetes as well as heart disease, high blood pressure, severe sleep apnea, gastro esophageal reflux disease and stroke. As with any major surgery it has plenty of risks, including excessive bleeding, infection, adverse reactions to anesthesia, blood clots, lung or breathing problems, and leaks in the gastrointestinal system.

After the surgery patients must deal with the long-term risk factors: bowl obstruction; dumping syndrome that causes diarrhea, nausea and vomiting; gallstones; hernias; low blood sugar; malnutrition; stomach perforation; ulcers; vomiting; and rarely death.

Then there are the financial and work issues.

“It has been a nightmare with insurance,” Slagal said. “This is the second time I have been scheduled for surgery and the second time I have taken time off from work.”

She was beginning to think it wasn't God's will for her to have the surgery. When she was just about to give up, the insurance company agreed to cover the surgery.

To deal with her behavioral problem she is getting counseling as a part of the weight-loss program. Once the program ends she has the names of counselors to talk to about her issue. She feels the challenge for her won't be taking the weight off, but keeping it off.

“I need to figure out what it is that makes me do this and how to come up with a coping mechanism,” Slagal said.

The surgery is all done laparoscopically and takes approximately two hours. During that time, the stomach is divided and a small pouch is created sealing off the majority of the stomach. A section of the small intestine is removed, and the remaining end is connected to the new stomach pouch.

Choosing the type of surgery

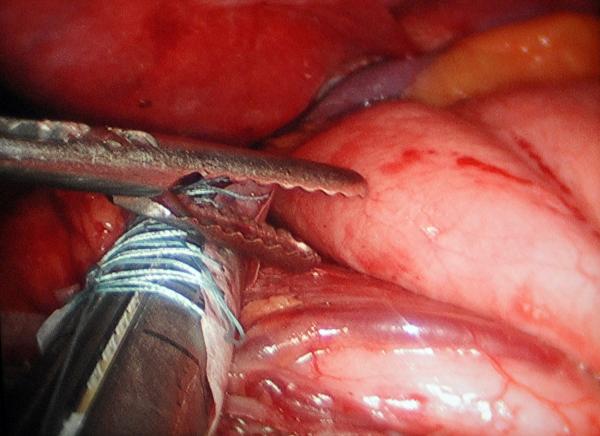

Slagal underwent a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery Feb. 13. Bariatric surgeon Dr. Dale Sloan, who heads up the Lutheran Health Network Bariatric Center, performed the procedure, which creates a small stomach pouch so little food can be eaten and bypasses part of the small intestine, reducing fat absorption. Sloan has been with the program since its start in 2005 and has performed 435 Roux-en-Y surgeries during that time.

The surgery Slagal had isn't the only one Lutheran's bariatric center offers; it also offers LAP-BAND surgery where a band is placed around the patient's esophagus and can be constricted or loosened by pumping fluid into the band. It is less invasive and can be removed, but is not always as effective in long-term weight management as the gastric bypass. Also offered is a newer procedure called the Sleeve Gastrectomy. It turns the stomach into a long tube by removing the majority of it. This is a newer procedure and Slagal said she didn't feel it had the proven track record the Roux-en-Y has. It is also new enough that some insurance companies will not cover it.

The Roux-en-Y gastric bypass can be done as open surgery or laparoscopically. It takes approximately two hours. During that time, the stomach is divided and a small pouch is created sealing off the majority of the stomach. A section of the small intestine is removed, about a yard, and the remaining end is connected to the new stomach pouch. An added plus to the surgery is it eliminates the part of the stomach where a hormone is produced that lets a person know he or she is hungry. Many patients totally lose the feeling of hunger after the surgery.

Sloan said when you are learning to do the procedure you must do a number of them as open surgeries before you are considered qualified to do it as a laparoscopic procedure. Sloan said he rarely does one as an open procedure anymore unless complicating factors exist for the patient. Sloan said recovery time is much faster with a laparoscopic procedure, in which several small cuts, or ports, are made in the abdomen to allow the placement of surgical tools inside the patient.

Many insurance companies will pay for the surgery because it significantly lowers the risk of other diseases caused by morbid obesity. All of these facts are presented to potential surgical candidates during an informational seminar that the LHN Bariatric Center holds several times a month. Having this type of surgery in many cases resolves or greatly improves respiratory dysfunction, hypertension, cardiac dysfunction, diabetes, arthritis, hyperlipidemia, urinary-stress incontinence and gastroesophageal reflux.

Effects of the surgery

Slagal's surgery took about two hours and went smoothly. It was one of three such procedures that Sloan performed that day. In the operating room the lights are kept low so the surgeon can easily view several TV monitors set up around the operating table. The surgery looks a little bit like tossing a salad in slow motion as the surgical nurse and surgeon manipulate the long handles of the surgical instruments in the patient's abdomen.Their eyes are focused intently on the screens, which show what is going on through a remote camera in the patient's abdominal cavity.

The surgery was on a Monday and by noon that Wednesday Slagal was ready to go home. But before she could leave, the nurse insisted she eat her lunch: very small portions of puréed chicken, tomato soup and vanilla pudding. After only several bites of each, she felt full.

Sloan said the most common problem that patients run into after the surgery is a stricture, in which the hole leading out of the newly formed smaller stomach has contracted. “Scoping” the patient solves the problem. The sphincter can generally be widened through this procedure, without doing invasive surgery.

Now more than six weeks after the surgery, Slagal is nearing the end of the intensive post-op support at the LHN Bariatric Center. The patients follow up their surgery at the center with a combination of exercise, nursing, nutrition, psychology, support and wellness, to help them develop good behaviors after their life-changing surgery. Each Thursday afternoon they meet for a two-hour session. Slagal is weighed every week. She has made friends with two other women who had surgery the same day she did, and they sit together whenever possible. They have vowed to keep each other on target.

The first few weeks were difficult. Slagal said they had warned her when she drastically reduced her food intake that the body's survival mechanism kicks in and makes the person want to hibernate. So she had to fight through the sleepiness and then deal with a body that no longer announced when it was hungry. Learning to eat the right amount of food and how often has been an ongoing challenge for her. She will be taking bariatric vitamins for the rest of her life because she can't physically get enough of the nutrients she needs through eating. She has to be aware of her fluid intake and when she takes it. She can no longer drink with her meals because it will fill her stomach up before she can eat the nutrition she needs.

Formerly big on fiber, the change in her diet and the smaller amounts she has been eating slowed her system down; by the fourth week after surgery she actually gained three pounds. But an increase in the amount of liquid she was taking in and a laxative solved the problem. By the fifth week she was feeling much better, and had lots of energy.

Slagal no longer is a Type 2 diabetic. She has begun a walking program with her best friend and is planning on signing up for the Fort 4 Fitness four-mile walk this fall. Since her surgery she has dropped 37 pounds. A former online shopper, she has begun to venture into the stores again, and is now enjoying it. She has already dropped several clothes sizes. Slagal said the result she least anticipated with the surgery was her total lack of interest in food. What once was a constant in her life has now become something she has to schedule in to remember. But overall Slagal has only positive things to say about her experience so far.

“Bariatric surgery has given me the edge I needed to regain my health and wellness,” she said.