While Fort Wayne wasn't the site of a battlefield like Gettysburg or a siege like Vicksburg or a mass burning like Richmond or Atlanta, it had its own significant role in the Civil War, which began 150 years ago Tuesday with the attack on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor in South Carolina.

On the eve of the war in 1860, Fort Wayne had a population of 10,388. By the end of war in 1865, the city had sent 4,103 men to serve in the armed forces; 489 lost their lives.

Numerous historical sources recount the participation of our city and county in the Civil War as well as how the war affected this area. Detailed summaries can be found in the chapter “Fort Wayne in the Civil War Era” by Allen County Public Library historian John D. Beatty from Volume 1 of “History of Fort Wayne & Allen County, Indiana 1700-2005” as well as “The Pictorial History of Fort Wayne” by the late B.J. Griswold.

Before the war, Fort Wayne favored Democrat Stephen A. Douglas in the presidential election of 1860. Douglas received 3,224 votes to Abraham Lincoln's 2,552. Lincoln scholar Mark Neely writes that it would be “difficult to find a city, north of Richmond, Va., that is, in which the Civil War president was less popular than he was in Fort Wayne.”

News of the firing on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, a month after Lincoln's inauguration, resulted in patriotic, bipartisan mass meetings in Fort Wayne and a rush of local men enlisting in the Union army. At the outset, people were convinced the war would be over in a few months with a decisive Union victory.

President Lincoln asked Indiana Gov. Oliver P. Morton for six regiments (775 men each). Beatty writes that Allen County declared it would guarantee three times that number.

The first Allen County regiment to reach the front was William P. Segur's Company E of the 9th Regiment, nicknamed the Wayne Rifles. When the unit left for Indianapolis, it got a rousing sendoff ceremony at the railroad station.

Beatty recounts that those who weren't discharged for “poor teeth” (strong teeth were needed for tearing off the ends of cartridges when loading guns) saw action at the Battle of Philippi in West Virginia on June 1. Henry W. Lawton, who later became a major general, was an orderly sergeant in Company E. He later received the Medal of Honor for heroism at Atlanta.

Other companies included their own special nicknames, such as William H. Link's Hoosier Guards, George Humphrey's Mad Anthony Guards and Orrin D. Hurd's Fort Wayne Union Guards. Link's and Humphrey's units became part of the 12th Indiana, organized May 11 at Indianapolis for a year enlistment.

Recruiting continued through the summer and fall of 1861. City leaders set up a formal campground for the muster of would-be soldiers, choosing a public area known as Camp Allen on the north side of the St. Marys River, today found on Camp Allen Drive off Main Street on the west bank of the river.

Recruiting at the camp was showcased July 4 with a 34-gun salute, the reading of the Declaration of Independence, addresses, prayers, a patriotic speech by banker Hugh McCulloch, a picnic and fireworks. More recruits flooded the new camp to enlist.

Editor and publisher Thomas Tigar of the Fort Wayne Sentinel praised Sion St. Clair Bass (who opened the city's first foundry) for organizing the 30th Indiana Infantry Regiment. And during the fall, there was a drive to organize another regiment, the 44th Indiana Infantry.

By then, the exuberant patriotism of April had started to wane. The nicknames began to disappear as local units became, as Charles Bragg and Lincoln scholar Neely wrote, “but small parts of a vast and numerically anonymous army, assigned regimental numbers rather than colorful nicknames.”

The 44th finally formed in November 1861. Hugh B. Reed, the Camp Allen commandant, became its colonel.

Meanwhile, Fort Wayne seemed to thrive in the environment of war. Railroad shops, foundries and factories did booming business to supply Washington's war needs.

The city's Republican leaders were rewarded with political appointments. Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase offered McCulloch the job as the country's first comptroller of the currency. In 1865, Lincoln asked McCulloch to succeed Chase as Secretary of the Treasury. It was, Beatty writes, “the highest-level government post ever attained by a resident of Fort Wayne.”

Besides the 30th and 44th, other regiments formed in August 1862 including a reorganized 12th Indiana, then a three-year regiment with Link as its colonel. There were also the 74th Regiment under Col. Thomas Morgan and the 88th under Humphrey. And some local men went elsewhere in the state to enlist.

The 44th played an important role in the capture of Fort Henry in Tennessee in the winter of 1862 as well as in the siege of Fort Donelson. Reed was reportedly wounded four times and had four horses shot out from under him.

The 30th, led by Bass, fought in the Battle of Shiloh on April 6-7, 1862, also in Tennessee. Bass' horse fell, and when he dismounted to tend to its wound, he was struck in the thigh by a musket ball. His death in a military hospital from complications a week later was a shock to people in Fort Wayne. His body was buried in Lindenwood Cemetery, not far from Camp Allen.

Link, head of the 12th, fought at Richmond, Ky., where he was struck in the leg by a Minieball, which shattered the bone. He remained in a military hospital with an infection for three weeks before dying Sept. 20, 1862. Link's body, too, was returned to Fort Wayne for a public funeral and burial in Lindenwood.

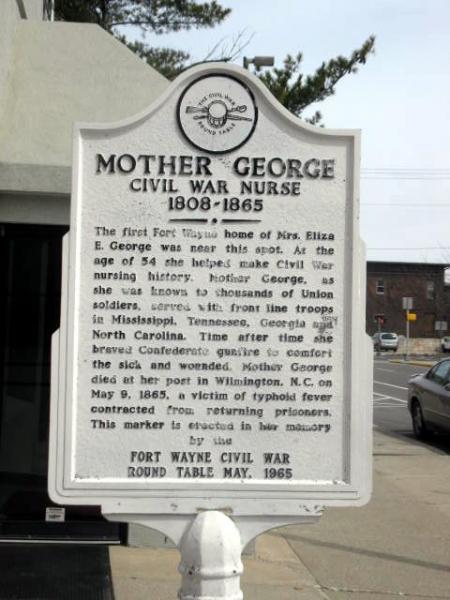

A few local women volunteered to serve the Union army as nurses. The best known was Eliza (Hamilton) George, whose daughter had married Bass. After the news of Bass' death, Mother George, as she became known, applied to the Indiana Sanitary Commission in January 1863. She was accepted, despite some hesitance from officials because she was in her early 50s.

Mother George served in Tennessee and Georgia, cooking, dressing wounds and consoling dying soldiers. After returning to Fort Wayne in 1864 for supplies, she went back to the front, where she died of typhoid in a military hospital on May 9, 1865. She was buried with military honors at Lindenwood.

The spirit of bipartisanship had long since evaporated in Fort Wayne. Republicans accused Democrats of being southern sympathizers, and Democrats accused Republicans of stripping them of their constitutional rights. The issue of slavery and the rights of blacks percolated throughout the war, and Fort Wayne residents held a mix of sentiments on the issue. When Lincoln came up for re-election in 1864, George B. McClellan, the former Union commander relieved by Lincoln, ran as the candidate for the Democratic Party. McClellan won Allen County by a 2-1 margin, with 4,932 votes to Lincoln's 2,244.

Fort Wayne had evolved into an industrialized city by the end of the Civil War. The war also helped it become a Midwestern hub of transportation, linking the central part of the U.S. to the East.

In 1884, historian Griswold reports, 5,000 Civil War veterans attended a reunion at Camp Allen, and in 1892 the Indiana Grand Army of the Republic Department's encampment was held in Fort Wayne and staged what was said to be the largest parade ever at a state meeting of the “saviors of the Union.”

After the war, elaborate tombstones were erected in Lindenwood over the graves of George and Bass. In 1894, a group of private investors raised funds to raise a bronze statue in Northside Park (now Lawton Park) as a memorial to all of Allen County's Civil War soldiers.