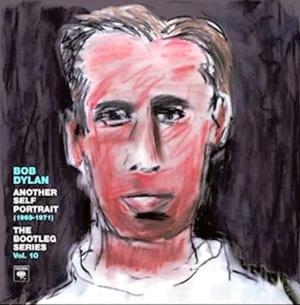

What is there to say about "Another Self Portrait"? If you're a diehard Bob Dylan fan, you have to have it. If not, you can probably take it or leave it. I have it. But even Dylan critics, I think, have to admire an artist who this late in his career can make Rolling Stone magazine get down on its knees to beg forgiveness: "We're soooo sorry we were so mean to him when the original 'Self Portrait' came out. Now we realize it was actually pretty good stuff."

I've never liked to over analyze music. You either hear an artist's voice and respond to it or you don't. All the things you can say about why he might be good or bad or overrated or underappreciated just amount to trying to universalize what is very subjective. Keep that caveat in mind as you're reading this.

I guess it's fair to say Dylan has always spoken to me, and I have listened. (No, never for me; let's have none of that "prophet of a generation" nonsense.) I learned to play guitar at Fort Hood, Texas, by copying the chords out of a Bob Dylan songbook, and the first song I learned to play all the way through was "Mr. Tambourine Man." It took days of fumbling to get the chord transitions down smoothly, and I must have gone through the lyrics 50 times in the process. I was no closer to grasping the meaning of the surrealistic images and obscure references at the end than I was at the beginning.

I guess it's fair to say Dylan has always spoken to me, and I have listened. (No, never for me; let's have none of that "prophet of a generation" nonsense.) I learned to play guitar at Fort Hood, Texas, by copying the chords out of a Bob Dylan songbook, and the first song I learned to play all the way through was "Mr. Tambourine Man." It took days of fumbling to get the chord transitions down smoothly, and I must have gone through the lyrics 50 times in the process. I was no closer to grasping the meaning of the surrealistic images and obscure references at the end than I was at the beginning.

Ever since, I've believed that a good song, like a good poem, should be simple enough to go straight to your heart and move you. A great one should be a little more mysterious. You think you might know what it means, but you aren't quite sure. By making the meaning elusive and hard to penetrate, the songwriter makes you bring something to the table. Trying to fathom the lyrics, you fashion your own meaning, which is so much more valuable than merely understanding the artist's. (Sorry about that, "Blowin' in the Wind" fans.)

"Another Self Portrait" contains material from 1969-71, five years and some from the songs in the book I learned from, a period when Dylan was producing "Self Portrait" and "New Morning" and hanging out with people like George Harrison, David Bromberg, Al Cooper and members of The Band, all of whom make appearances on the album. It's an amalgam of selections from the folk song catalog, covers of contemporary artists Dylan liked and outtakes, alternate versions and half-finished snippets of his own creations. You can hear folk here and rock and blues and stuff that goes back further than all of it from a period when the artist was still discovering and reinventing his musical journey.

You should know that the album is mostly rough and uneven; there are false starts and stumbles, tentative versions that don't work of finished songs that certainly did (like "Went to See the Gypsy" and "I Threw it All Away") and cuts that just seem odd, like horn and strings overdubs on what would otherwise be just primitive three-chord progressions. And in a few places, it's obvious the musicians are just having a good time fooling around in the studio.

But roughness is sort of the whole point of the albums in the Bootleg series, of which this is the 10th. An artist's oeuvre is usually just what he wants you to hear, after all the rewriting, polishing and post-production ruffles and flourishes. With Bootleg, Dylan has shown us all the raw material that went into the finished product. We can see the influences on a major musician, how he grows as he processes them, even the mistakes he made along the way.

Dylan has been among the most enigmatic of our cultural icons, mostly because he's wanted it that way. (Hunt up his first Playboy interview for a hilarious episode of deliberate obfuscation, misdirection and downright tall-tale lying with an interviewer who was absolutely clueless; it was even more satisfying than the 123rd interview with George Jones in which the credulous reporter breathlessly revealed he was going to quit drinking, and he really, really meant it this time.) If you really want to know Dylan, skip all the writers trying to get into his head. Listen to Bootleg and hear how the artist developed. This is Dylan without the personas.

(As an aside, I think it's almost brave for Dylan to have revealed so much of his influence from the folk tradition. He's been criticized a lot for "borrowing" from other artists and their songs, if not out-and-out plagiarizing. But lifting and adapting and passing along is very much a point of the folk tradition -- hell, it's the whole point; let's gather around the campfire and swap the old stories -- we'll deal with that pesky Internet in a few centuries. Dylan is saying, I think, yeah, I've built from the past, and these are the building blocks I borrowed. Deal with it.)

If you can get through the rough spots of "Another Self Portrait," you should find some real gems. Check out the fatalistic existentialism of the traditional "Copper Kettle" and "In Search of Little Sadie," the naive love-will-conquer-all-wandering-ways optimism of the cover of Eric Andersen's "Thirsty Boots," the yearning for meaning in Dylan's own "Pretty Suro" and "When I Paint My Masterpiece" (I think it means "when I finally quit screwing around and become who I'm supposed to be; what do you think?) As someone writes in the liner notes (yes, there are actual liner notes), everyone will find a particular song in this 35-track collection around which to build an understanding of the whole. For me, it was one of the most unadorned entries, the traditional "Spanish is the Loving Tongue," which is just Dylan singing and playing the piano. I read where one critic dismisses it as an inferior version of Dylan's own "Boots of Spanish Leather." I don't know why that song grabbed me, but it did. It is, after all, just an easily understood "love smote me" anthem, never mind my fondness for the enigmatic. Go figure.

Anyway, a pleasant visit with an old friend. The album took me disappearing down the smoke rings of my mind, down the the foggy ruins of time. Or, as an editorial writer might put it, the album scattered the accumulated detritus of quotidian obligations and enabled me to reconnect with my inner peace.

(Another little aside here. If you want to really get Dylan and the music of that era, watch Martin Scorsese's "The Last Waltz" with The Band and the best of their musical friends. I swear, I don't think those guys ever collaborated or even tried to work as a team. They were just up there on the stage each doing their own thing. But, lord, it did all fit together beautifully.)

Most of the critics who say Bob Dylan is overrated (and I've stopped trying to keep track of them) miss or deliberately overlook an important point. Most of us are trying to figure out the universe and our place in it and, heaven help us, a few of us even presume to explain it all to others. We look for inspiration where we can find it, and Dylan has spoken to countless thousands of us in that quest.

Oh, and this album is of course from materail Dylan created before he started sounding like a frog, so there is that big bonus.

I'll let you in my dreams if you'll let me in yours. Bob Dylan said that. You find your muse, and I'll find mine. I said that.